Challenge Accepted: Taking a deeper look at Tetris

Are there better feelings in games?

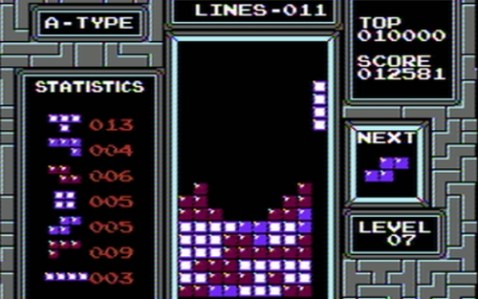

Tetris is, in every way, one of the simplest games ever devised. It’s also one of the most successful, perhaps the most ubiquitous game ever created. Everyone understands Tetris as a game concept more or less from the womb, and subsequent years have seen endless numbers of ports, adaptations, variants, and so forth. All based off of the very simple, straightforward, and almost trivial challenge – stack lines of blocks, don’t let the lines reach the top.

The simplicity of the game belies the fact that there’s actually a wealth and depth of challenge available in the game. It finds new ways to challenge you, perpetually, so that even though you’ve doubtlessly played the game for ages, every single game becomes a new challenge and something to be anticipated and enjoyed. It engages you on almost every level, and the result is a game that’s fascinating to both play and understand on a deeper level.

The Final Fantasy Project: Final Fantasy V, part 5

Artwork from a sketch by Yoshitaka Amano

I made a passing comment at the end of the last article that I think deserves to be unpacked a little bit, because it’s the basic problem that every single Final Fantasy game since Final Fantasy V has been trying to solve. How do you allow characters to share abilities while still making all of the diverse classes available be worthwhile for something unique?

The reason this comes up is because of things like Beastmaster. As a class, Beastmaster is pretty awful. Its big tricks aren’t useful, it doesn’t provied more damage or healing than any other class, and the one thing it has in its favor is the ability to control an enemy. That sounds pretty screamingly useful, to boot… but then you realize that there’s no need to actually put that ability on a Beastmaster. Why would you not just grind for a little bit on Beastmaster, unlock Control, and then never touch it again?

Such is the plight of several jobs in the game. Such is, in fact, the plight of several jobs in every game, but this is the point where the struggles begin. In Final Fantasy III, there were a couple of classes you could get away with never using, but a majority of those jobs were useful somewhere even if you weren’t likely to use them from start to finish. In Final Fantasy V, even decent jobs pale compared to the jobs that combine nicely with other jobs.

Titular goals

Sometimes, of course, there’s no actual catching involved. That’s when you know the game is mocking you.

Have you ever thought about how weird it is that Pokémon doesn’t actually care if you catch all of the various little monsters?

I mean, it does, totally. The series tagline is “Gotta catch ’em all!” with more exclamation points added depending on how the writer feels that day. Obviously the game cares if you do, in fact, catch them all. Failing to catch them all means that when you reach the end of the game, you…

Well, that’s just it, isn’t it? Even if you do have hundreds of pokémon by the end of the game, you’re still not going to be using the vast majority of them. Even in the first games, you couldn’t be using the vast majority of them, since you had 150 total monsters and six spaces for your field team. Catching literally every single monster does not award you anything different except more breeding options, and the vast majority of the monsters you can potentially catch aren’t useful for that, even. The game in no way cares about you catching them all… except for that tagline.

Demo Driver 8: Letter Quest: Grimm’s Journey

I fought a werewolf with nothing more than weaponized words. That’s what I did today.

Bookworm Adventures was always weird. In a good way, mind – I think the weirdness of the very premise had a charming quality, albeit happily disconnecting from anything resembling reality by simply deciding that forming words deals damage and going from there. It is, in many ways, the logical precursor to games like Puzzle Quest and Gyromancer, games with love for the RPG model but with an eye toward making the mechanics of fighting things a bit more unusual.

You cannot, however, call it the “logical precursor” to Letter Quest: Grimm’s Journey without being exceptionally generous with your use of that term, because it’s the same damn game. Letter Quest, top to bottom, is so close to Bookworm Adventures that calling it even a spiritual sequel is a bit too gentle. It’s the same core game with a slight facelift, a different look to it, and new challenges for you to clear through as you plod along through some story or another that’s not terribly well-defined and mostly exists so you can kill monsters with letter tiles.

That’s really not to its detriment, though.

You don’t want your characters to like what you like, usually. At least not solely. One of the joys of roleplaying is stepping into the shoes of someone different than yourself, which doesn’t work in the event that your character is basically you with a race-lift and possibly a gender shift. Since one of the things that we use to define ourselves is the existence of distinct tastes from other people.

You don’t want your characters to like what you like, usually. At least not solely. One of the joys of roleplaying is stepping into the shoes of someone different than yourself, which doesn’t work in the event that your character is basically you with a race-lift and possibly a gender shift. Since one of the things that we use to define ourselves is the existence of distinct tastes from other people.