Hard Project: Tech games

I can’t be too hard on a game that only set me back fifty cents, but still.

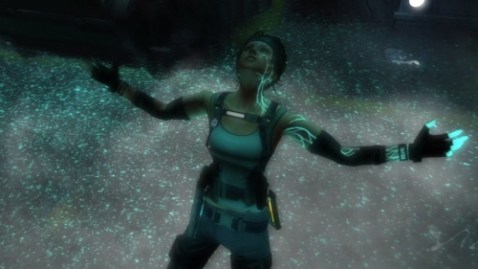

Hydrophobia: Prophecy is not a very good game overall, but it sure is an amazing tech demo for water physics. The way that water behaves in that game is absolutely amazing. It flows believably, moves your character around like water ought to, and generally serves as a clear indicator that the majority of work was on creating the best damn water simulation ever. Actual gameplay and stuff like that was a secondary concern at best. Which is fine; it joins a long list of tech games that aren’t very good.

Tech games are exactly what they sound like, demonstrations of technology that have a game wrapped around them. They are also almost universally terrible. In fact, there’s only one company out there which has managed to produce good tech games with any consistency – Nintendo. And there’s a good reason why, wince that ties into both why tech games are a hard project and why it’s so difficult for third-party developers to make a good game for a Nintendo console released in the past twenty-ish years.

A story of the vagrant

You could be forgiven for thinking that this game’s plot intimately involved both of these characters with one another.

Whenever I start writing anything about Vagrant Story, I have to force myself not to start gushing about the elegant perfection of the weapon system. I mean, it’s simple – six monster families, using a weapon on one builds up bonuses against that monster type, and your goal becomes stacking up that bonus while you reforge that weapon into more potent forms over time. But then you consider that weapons have different damage properties, and you want to try and build a weapon using properties that most monsters of that family will be weak against, and then whoo, I’m down the hole again and I wake up to find I’ve ranted about the system for hours.

It’s a simple, elegant, brilliant design. So much of the game is a simple, elegant, brilliant design. On one hand, it’s almost criminal that the game has never received any kind of sequel, even any sort of larger story resolution beyond getting retroactively thrown into the overall Ivalice continuity (although Yasumi Matsuno has gone back and forth on that one). But on the other thand, it’s kind of a good thing. It somehow makes the game work better that it never became iterative, that all of it is contained solely herein, even if you wish there was more.

Challenge Accepted: Difficulty patterns

Giving the player ultimate control over the curve has both benefits and drawbacks, starting with the fact that players have the right to just opt out of much challenge there.

One of my favorite things to say about a game is that it has a difficulty curve bordering on a flat line. It’s a remarkably elegant way of pointing out that a game doesn’t really change its difficulty over time, that if you can clear the first level without too much trouble the next dozen won’t give you much more or less challenge. It’s not necessarily something that you want to be the case with a game, but it does happen.

It also presupposes that difficulty in most games is at least roughly a curve, but it can really be in lots of different shapes. If you want to get super technical, the shape can even vary from player to player, but that’s not the road I want to walk down today. No, today I want to take a look at how it works when you start tracking the challenge of a game over time, how the ebb and flow affects the game as a whole. Sure, we’ve played games where the curve resembles a flat line (or a vertical one), but even the idea of a difficulty curve means that there’s a different rate of change over time.

Duration metrics

If discs had anything to do with quality, Vagrant Story would be a worse game than Legend of Dragoon. The mere suggestion is kind of offensive.

I remember the exact moment when I decided that bragging about how many discs your game was on was a pile of crap. It was when I paid money for Legend of Dragoon.

There’s no way around the fact that Legend of Dragoon is a bad game, and at its best moments it’s just Final Fantasy by way of Power Rangers, a line I am reluctant to write because it sounds potentially awesome and I don’t want Legend of Dragoon to sound awesome. But that isn’t the point; the point is that I remember playing the game, looking at the back of the box, and thinking, “Did I just buy this because it was an RPG with four discs?”

My defense would come down to the fact that I was seventeen and dumb as hell. Still, though, it makes you think about how duration is a selling point for games, not just for crap games that Sony desperately wants people to buy but for all sorts of games. Hours of gameplay. Number of levels. Number of classes, companions, combination attacks, areas, and so forth. And that’s kind of nonsense.

Demo Driver 8: Satazius

Considerate enemy armadas build ships that are designed to be dangerous from exactly one angle and utterly non-threatening in every other configuration.

It’s weird to see a game that’s specifically targeting your own nostalgia when, by and large, you steer clear of gaming nostalgia. I’ve been playing video games for a long portion of my life, and I know that I’m not immune to the siren song of old loves, but I like to think I’m also aware of the fact that the past of video games is filled with missteps, bad decisions, and stuff that made sense at the time but not now. My affection for the past is rarely within sight to be targeted at all.

And then, of course, I find a game that is a direct throwback to one of my longstanding loves, a shoot-’em-up in the mold of Gradius, Darius, and R-Type. While the master genre never died, I’ve noted in the past that it’s tapered off into a steady stream of bullet hell shooters, which I have less affection for. Satazius, by contrast, feels very much like a familiar variant on old tropes, so much so that I had to double-check that it isn’t a remake of something. They found my one weakness.